Michaela Melián

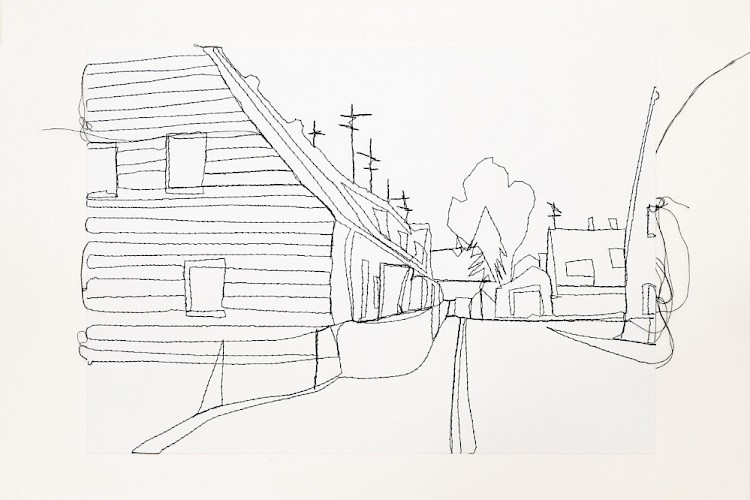

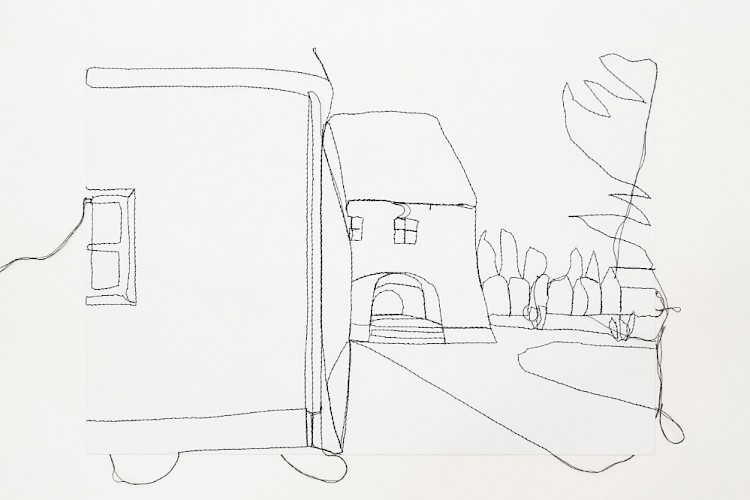

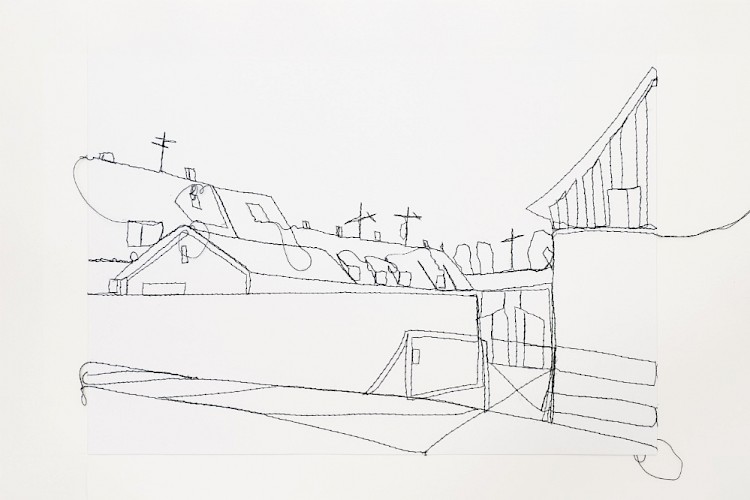

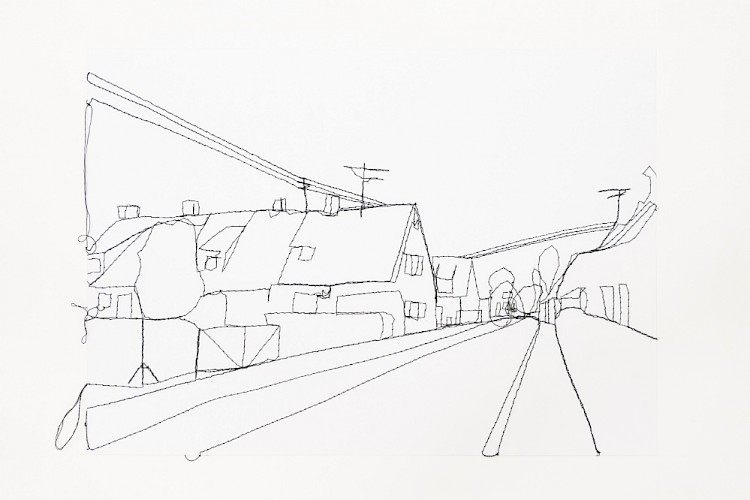

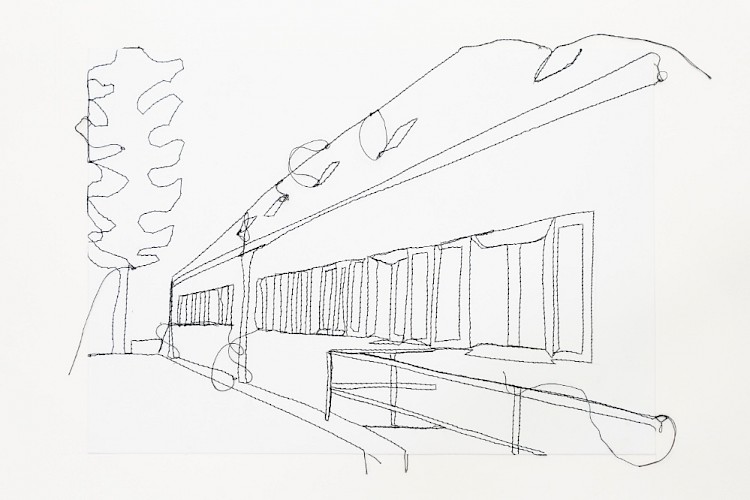

Life as a Woman | 2001 | ink on paper | 40 x 30 cm

Michaela Melián (* 1956, München) ist Künstlerin und Musikerin. Sie ist Mitgründerin der Band F.S.K. und war bis 2023 Professorin für zeitbezogene Medien an der Hochschule für bildende Künste (HfbK) in Hamburg. Typisch für Meliáns Arbeiten ist die Verbindung von Kunstobjekten mit Klang. Gleichzeitig spielt die Auseinandersetzung mit Geschichte und Nachleben des Nationalsozialismus in ihrem Werk eine zentrale Rolle. In ihrem Hörspiel Föhrenwald (2005) setzte sie sich mit dem dort ansässigen Konzentrationslager auseinander, in Memoryloops (2008) schaffte sie einen virtuellen und soundbasierten Gedenkort für die Opfer des Nationalsozialismus in München. Sie wurde mit zahlreichen Preisen ausgezeichnet, darunter dem Hörspielpreis der Kriegsblinden (2005), dem Grimme-Online-Award-Spezial (2012), dem Edwin-Scharff-Preis (2018) und dem Rolandpreis für Kunst im öffentlichen Raum (2018).

Works

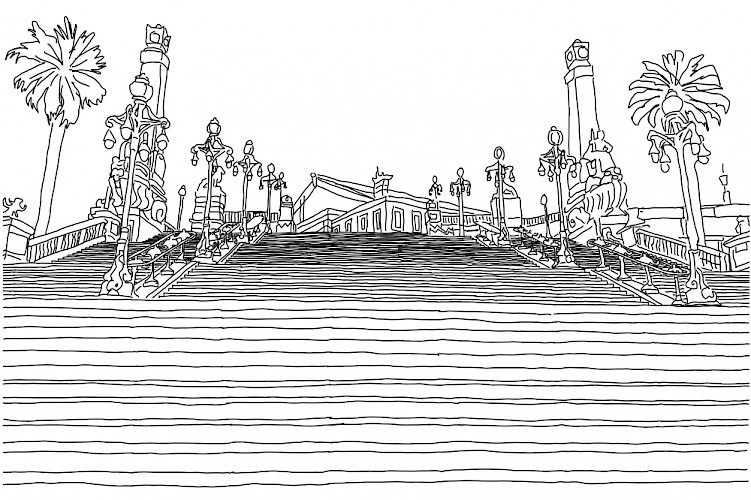

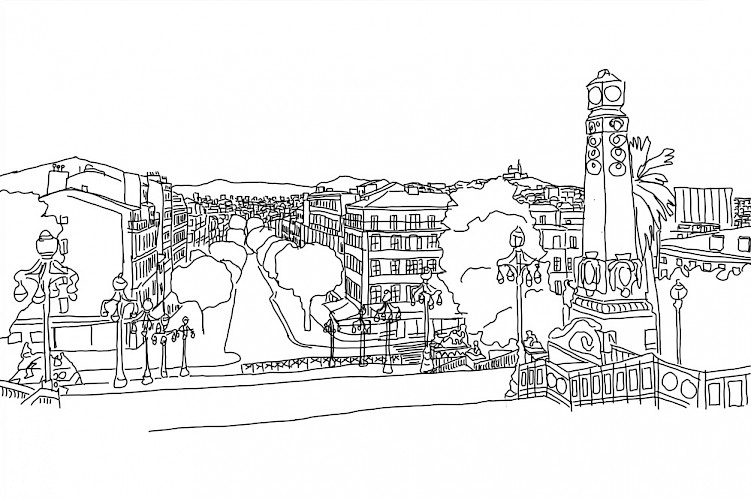

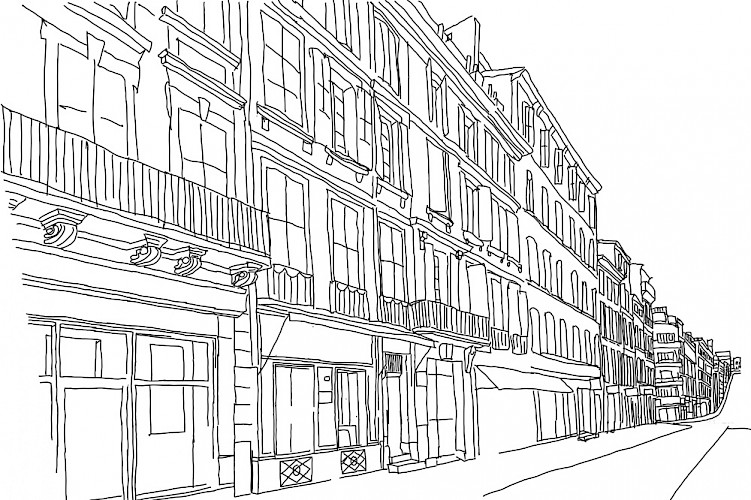

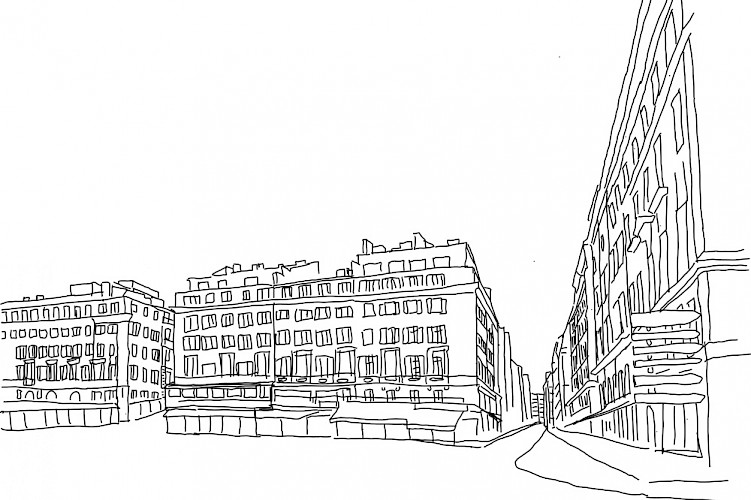

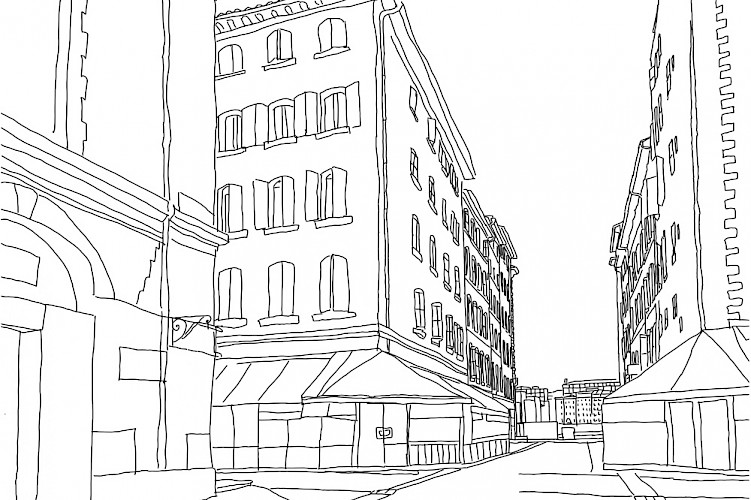

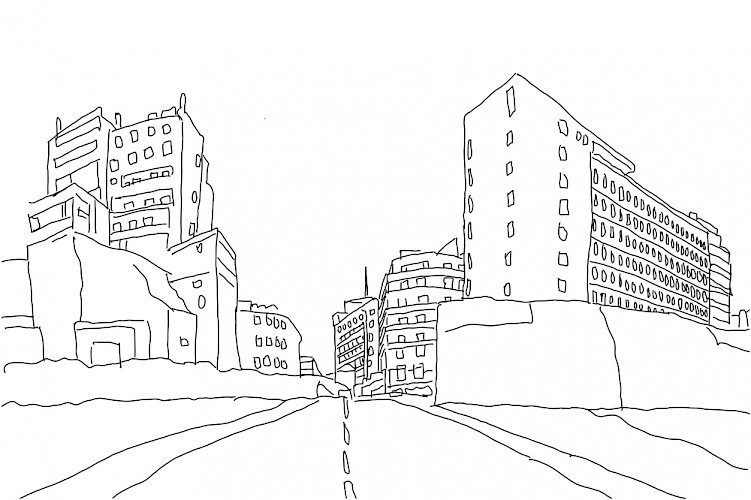

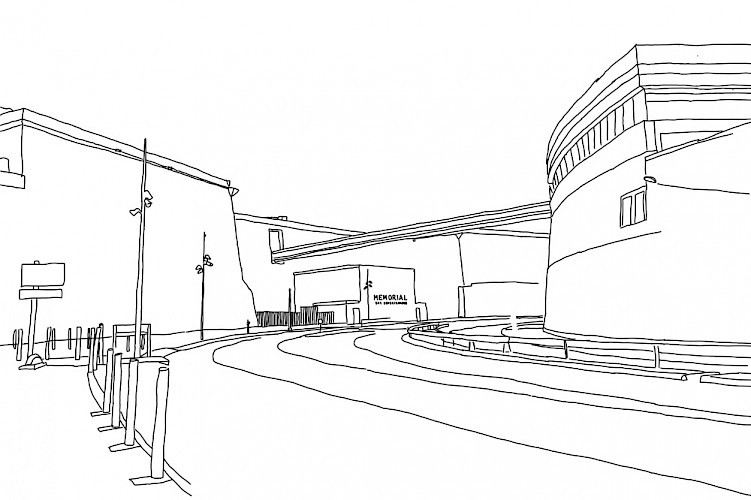

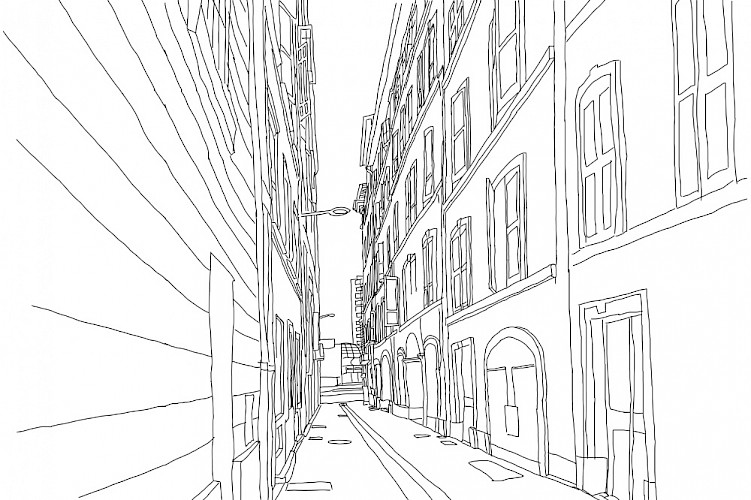

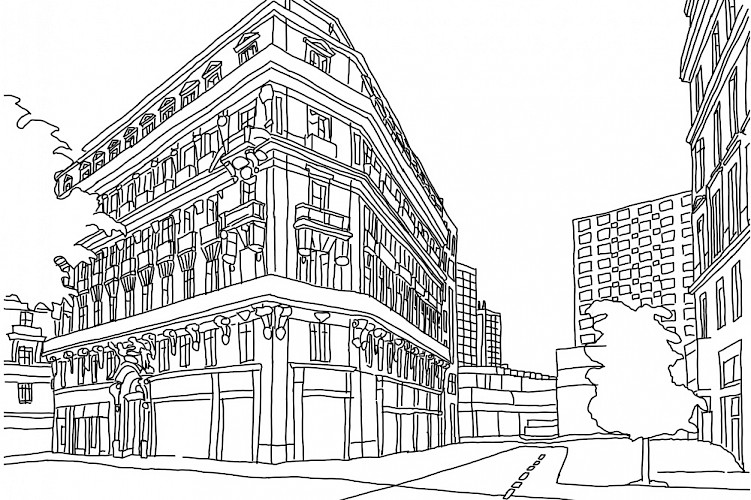

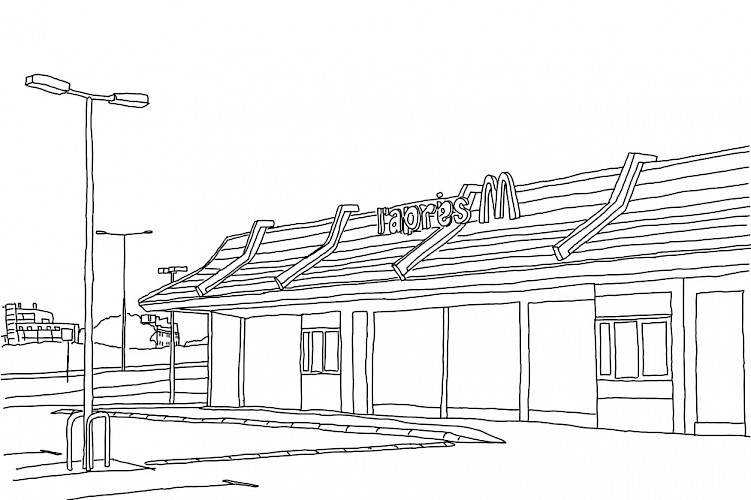

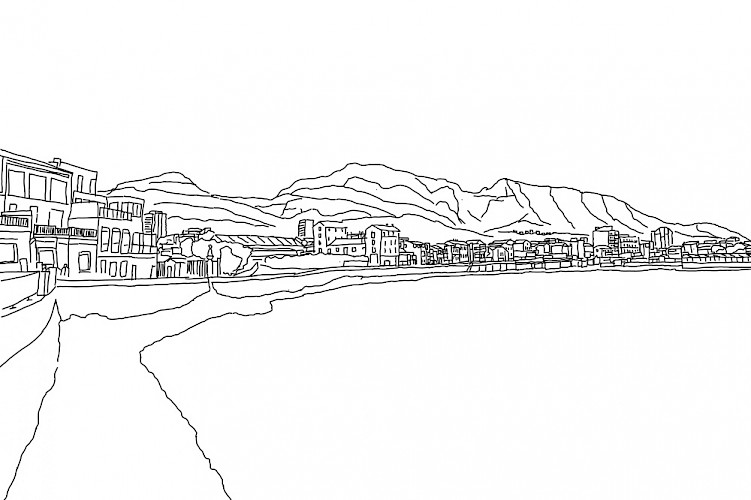

Passages (Chapter I, Marseilles)

Bringing Gustav Metzger Back to Nürnberg

Ulrichsschuppen

Tania

Maria Luiko, Trauernde, 1938

Girl-Kultur

Herminengasse

Lunapark

Hausmusik

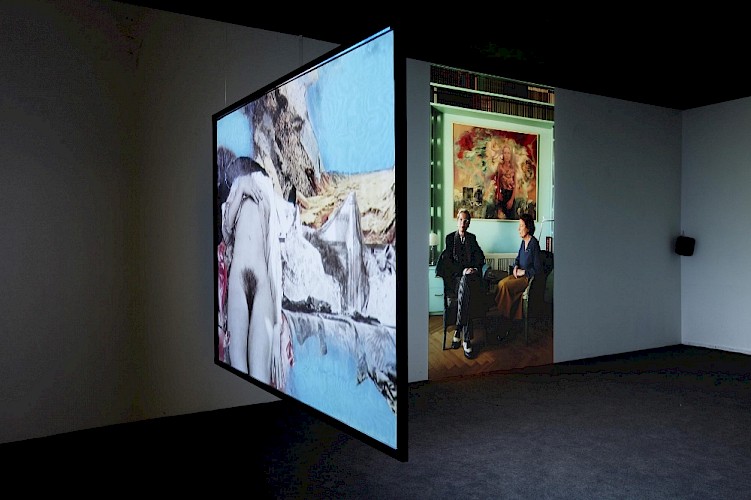

Sylvia Bovenschen und Sarah Schuhmann

Studio

ESR

Triangel

Föhrenwald

Panorama

Lost Highway

Maria Magdalena

Life as a Woman

Leopard II

Festung

Bertha Pappenheim Projection

18 digital drawings | 2025

Won Jin Choi: Passages - Passagen, 2025

Marseille resists interpretation. Or rather, there are as many interpretations as there are individuals. Most of its inhabitants descend from those who came from elsewhere. Over the centuries, the Old Port has absorbed or rejected its offspring in the wake of invasions, epidemics, gatherings, reunions, opportunities. In the mid-20th century, it was war that drove Europeans in search of a new beginning onto its quays. In Anna Seghers’ novel Transit, written after her stay in Marseille in the 1940s, the narrator wanders between cafés, consulates, and hideouts, surrounded by other lives in transit. The movement of his companions in fortune is circular, haunted by the feeling of arriving either too early or too late, and by the sense of an eternal return.

Passagen – Passages extends this movement into the present, where Marseille is defined less by arrival or departure than by transit. The project explores how the city and its places bear the marks of time, how memory inhabits the streets, and how both are constantly being rebuilt. Beneath or above the asphalt, History is trampled every day.

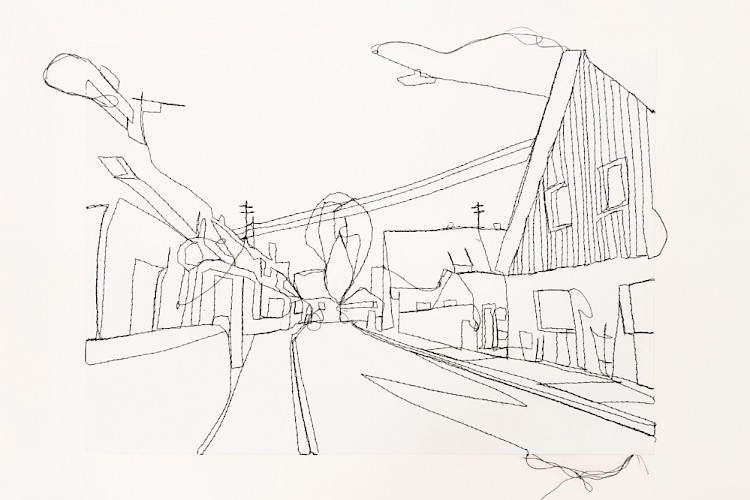

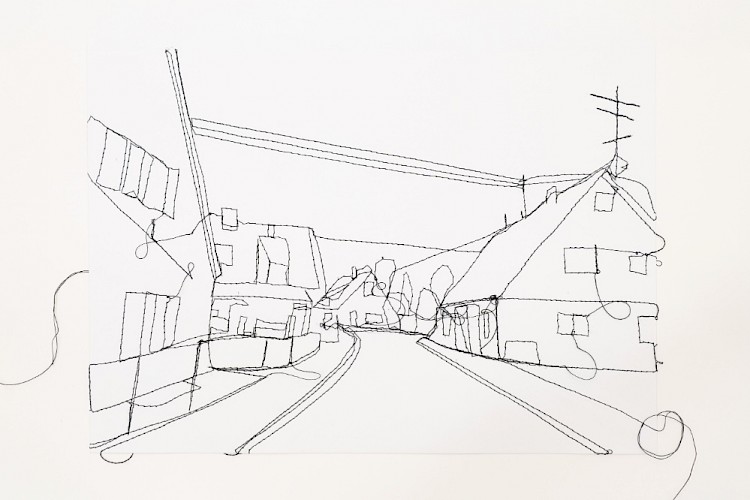

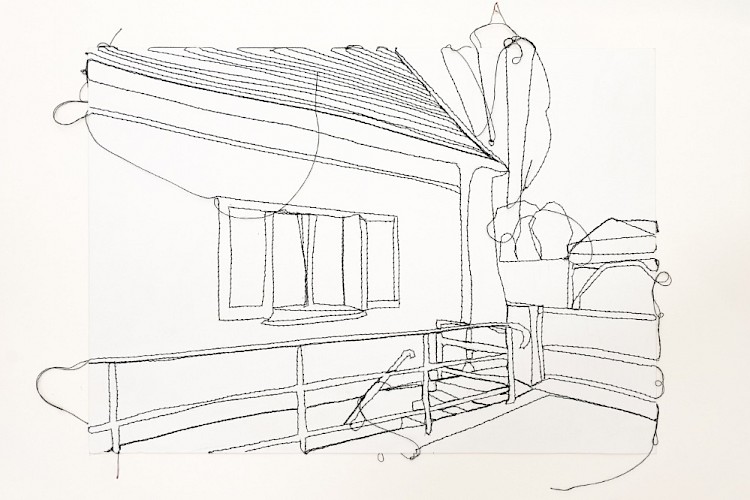

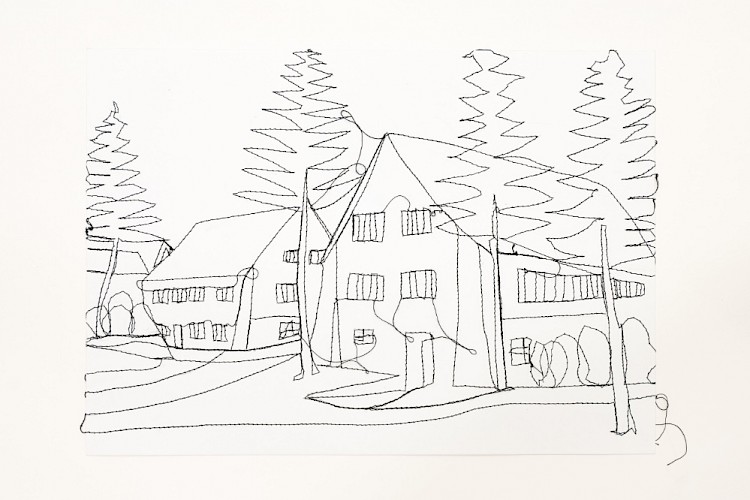

At the heart of the project lies the work of Michaela Melián, German artist and musician, whose longstanding family ties with the south of France intersect with professional connections established in the city. For Passagen – Passages, she created 17 black-and-white drawings, first exhibited at La Blancarde station, a place where one waits, departs, or returns. They act like signals, inviting one to pause or to continue on one’s way. After some time, this public installation of drawings will move to a neighboring district, traveling like the figures it evokes: displaced, unstable, elusive.

The project was born from traces. There are letters, gestures, itineraries, names slipping out of History. Traces left by lives such as those of Helen Hessel, Albert O. Hirschman, or Jesús Argemi Melián. The artist’s research asks how these stories are transmitted, refusing to fix meaning, letting the city’s fugitive logic guide the process.

There is no central exhibition, no gathering of works in a single place. Passagen – Passages unfolds across an open field: a drawing, a voice on the radio, a printed fragment, a film, a few conversations, a story caught on the fly. These isolated gestures invite reflection on what persists in a porous city shaped by transit. The drawing is altered, like the narratives themselves. What the archive cannot contain, the city still carries. A public bench. An anonymous face. A walk without destination. We circle around what cannot be named. In this circular movement, things ultimately endure.

Tania, that is the fighting name of Tamara Bunke. Bunke was born in Buenos Aires in 1937 into a communist German-Jewish family in exile. After the war she moved with her parents to the GDR, joined the FDJ and later studied at the Humboldt University in Berlin.

In the 1960s, she left the GDR, first to Cuba and then joined the guerrilla group led by Che Guevara. Che Guevara’s guerrilla struggle in Bolivia, where she was was ambushed and shot in 1967. For the work complex TANIA, Michaela Melián intensively researched reports, events and places from Tamara Bunke’s / Tania’s life. In her life story, the major themes of the 20th century: National Socialism, war, socialist modernity, emancipation and liberation. Her biography, however, can only be unreliable narratives, falsified documents, cover identities, projections and suggestive documentations and permanently eludes elucidation.

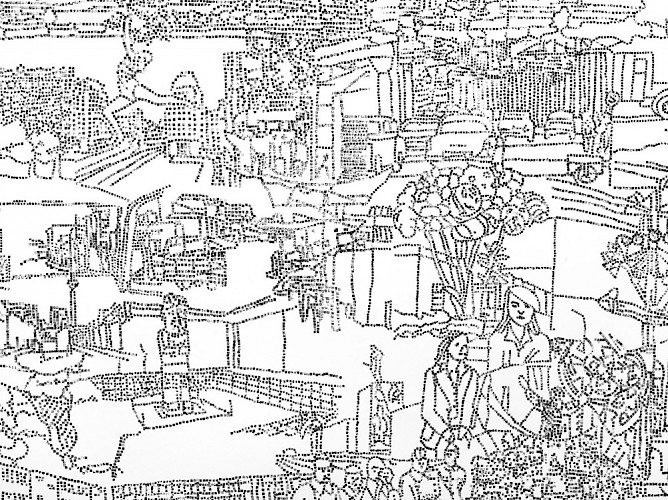

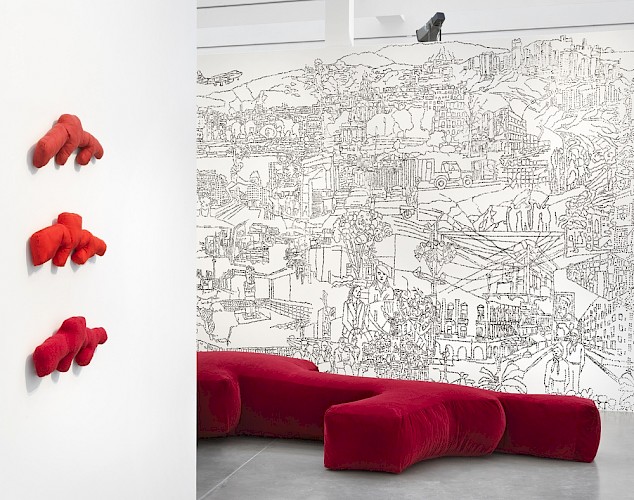

Melián does not censor Tania’s representations, but collectes as much material as possible in order to channel it into an artistic-intellectual process that makes it possible to thematise the political and medial conditions of these representations. Models for the total of 250 drawings that Melián made as the basis for the new mural TANIA, are excerpts from documentary films, views of La Paz, where Tamara Bunke worked as an agent of the Cuban secret service in the midst of Bolivia’s political of indigenous sculptures she made in her camouflage identity as ethnologist Laura Gutiérrez Bauer, current Google Street Views of the places where she lived, among others. Berlin of socialist modernism, postcards from Western European capitals that Bunke had during her training as a spy or agent, photographs of the oil production towers in Cuba, of the Bolivian Andes and of the funeral service for Bunke at the ZK der SED with the speaker Anna Seghers. Melián digitally assembled the drawings into a dense fabric, which is dissolved into pixel points stamped on the wall in repetitive, collective handwork with eraser and stamped onto the wall. Melián realises thematically and in terms of formal design, Melián thus realises a image and draft, archival document and vision of the future, information and vision of the future, information and noise.

In the work complex Tania, central processes and themes from and themes from Melián’s work and also from this exhibition. These include the potentially infinite research, which a fanned-out and unfinished view of history and biographies. history and biographies. These include the series of processes of reproduction and media translations – from and media translations – from film to drawing to Photoshop to Photoshop or from photo to verbalisation to drawing. to drawing. In this way, Melián can independently the artist’s „ingenious stroke“, Melián can thematise the conditions under which the conditions under which identities and spaces are and represented. Traditional artistic forms of representation

of identity and space are the and the veduta (view of a city), of which there are several on the of which can be found on the mural Tania. How is identity, how do we want to live, what is the space that is granted, that is fought for? These are questions around which this work, but also other works in the exhibition, such as the Gobelin Girl culture, revolve around.

The site-specificity of the work is also to be seen as an engagementwith the history and social reality of the city of Berlin and its artistic genres. In its form, the mural is not only related to South American murals, but also to socialist mosaics, one of the most famous of which is From the Lives of the Peoples of the Soviet Union on Berlin’s Karl-Marx-Allee, where Bunke’s parents also lived.

The work is a further development of the 2004 Werkleitz-Biennale in Halle on the same theme. In the update, the views condense into a thicket that is impenetrable in places. The mural does not offer a sovereign, possessive view of the metropolis on the red threads of the world; rather, identities, places and histories dissolve again and again into unknown figures, forms and indistinct flickering.

The second part of the Tania installation and central to the complex of works in this exhibition is the newly developed sound installation

TANIA, which deals with the musical canon around Tamara canon around Tamara Bunke. For this work Melián assembled sound fragments of self-recorded protest songs of of 10-20 seconds in length: Die Internationale, Die Moorsoldaten, Bella Ciao or the anthem of the 26th of July, also known as the Cuban as the Cuban Revolutionary March. In addition there are from musical cultures that Tania researched in her cover identity as an anthropologist. The recordings with Inca flutes refer to the recordings found in Tania’s backpack, which she backpack she was carrying when she was shot. The recordings are displayed in the exhibition room over a dozen or so pressurised chamber loudspeakers, like those as you would hear on public transport.

The Old Botanical Garden was built at the beginning of the 19th century according to the plans of Friedrich Ludwig von Sckell. From 1854 onwards, the garden was also the site of the Munich Glass Palace, where countless important exhibitions of contemporary art took place. In 1931, the Glass Palace burned down.

In 1935, the National Socialists commissioned the sculptor Joseph Wackerle and the architect Oswald Bieber, two artists included on Adolf Hitler’s „God-gifted list,“ to redesign the Old Botanical Garden. The site, which was home to the Glass Palace, — at the time Munich’s most important exhibition venue for contemporary art — had initially been designed as a place of recreation, education and culture for the citizens of Munich. The construction measures carried out by Wackerle and Bieber, however, visibly aimed to transform the park into a place shaped by National Socialist ideology that closely connected with the adjacent Nazi party district around Arcis-, Briennerstaße and Königsplatz.

Statues of Neptune had been a popular motif for decorative fountains since the Renaissance. The Munich fountain was directly modeled on the Fountain of Neptune in Florence, the Fontana del Nettuno in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, in which the figure of Neptune became the symbol of a contemporary and earthly ruler.

The Neptune Fountain by Wackerle and Bieber is formally aligned with the central axis of the Munich Palace of Justice. During the National Socialist era, countless politically motivated court proceedings took place in this building, where people accused for ideological reasons faced occupational bans, concentration camps or death sentences.

For the series „past statements. Denkmäler in der Diskussion“, organized by the Cultural Department of the City of Munich, the monstrous figure of Neptune is temporarily cloaked in tarpaulin. The tarpaulin is printed all over with the motif of a hand print by the Munich artist Maria Luiko. The woodcut from 1938 which bears the title Mourner shows a head covered with a cloth. The only physical indication of a mourner are the hands of an anonymous woman holding the cloth and a hint of a blouse with a floral pattern.

The artist Maria Luiko created this Trial Print No. 1 of Woman, Mourning in 1938, one year after Wackerle and Bieber’s Fountain of Neptune was built on the site of the Glass Palace where Maria Luiko had regularly exhibited her paintings between 1924 and 1931. At this time, however, Maria Luiko, a German Jew, was only allowed to pursue her artistic activities in an extremely limited form (that is, only within the framework of the Jewish Cultural Association). The location of the Jewish Cultural Association on Promenadeplatz 12 in Munich was in the immediate vicinity of the Old Botanical Garden.

Maria Luiko was born Marie Luise Kohn in Munich in 1904. She studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich from 1923 to 1928 and simultaneously at the Munich School of Applied Arts. After her studies, Kohn, who chose the artist’s name Maria Luiko, was very active as an artist, producing drawings, water colors and oil paintings as well as silhouettes, lithographs, woodcuts and linoleum prints; her works were shown in important group exhibitions in galleries and in 1931 even in New York and Denver/Colorado. After 1933, Kohn, who was a member of several artists‘ associations, was excluded from the Reichsverband bildender Künstler, which amounted to a professional ban, and was no longer allowed to use her artist name Maria Luiko. Her parents‘ wholesale business was forcibly closed down and expropriated in 1938. After all attempts by the family to leave Germany had failed, Marie Luise (Maria Luiko), Elisabeth and her mother Olga Kohn were deported in November 1941 from the Milbertshofen freight station to Kaunas in Lithuania along with almost 1,000 other people persecuted as Jews by the Gestapo. They were murdered by the SS and their accomplices just a few days after their arrival on November 25th.

Maria Luiko, Trauernde (Woman, mourning), 1938 Woodcut, proof no.1, Courtesy of the Jewish Museum Munich, Maria Luiko Collection, Photo: Franz Kimmel

Sound track # 202 of Memory Loops memoryloops.net. This sound track can be found on the drawing of the city map on the internet on Loristraße 7, the residence of the Kohn family, Blutenburgstraße 12, the studio of Maria Luiko and on Promenadeplatz 12, the address of the Jewish Cultural Association in Munich.

The project is part of the program „past statements“, a cooperation between Public Art München and the Institute for City History and Culture of Remembrance, City Department of Arts and Culture.

http://www.publicartmuenchen.de

Michaela Melián dedicates her work Herminengasse at the northern exit of the Schottenring subway station to the Jewish victims of National Socialism who lived in the street of that name in Vienna’s 2nd district.

A research study made for the project established that, between 1938 and ’45, 800 Jewish men and women who permanently lived or were assigned temporary quarters in Herminengasse were eventually deported by the Nazis. Melián traces the fates of these individuals by drawing lines that lead from the residential houses in Herminengasse to the various concentration camps.

On the edge of the wall pictures, the concentration camps are listed not in geographical but in alphabetical order. The houses of Herminengasse are not realistically depicted, but rendered as bars in an information graph, which refer to the total number of 1322 Jewish people living in that street over those seven years. Underneath, there is a structure of gray lines that visually represent the railway network at the time.

On the way to the subway station exit, you literally pass through Herminengasse—with the left wall picture showing the houses on the left side, and the right picture those on the right side of the street.

On the basis of facts and data collected, a web of lines was created that visualizes subtly but clearly the commited injustice.

Astrid Wege

Lunapark

Published in: Michaela Melián - Electric Ladyland, Lenbachhaus, 2016

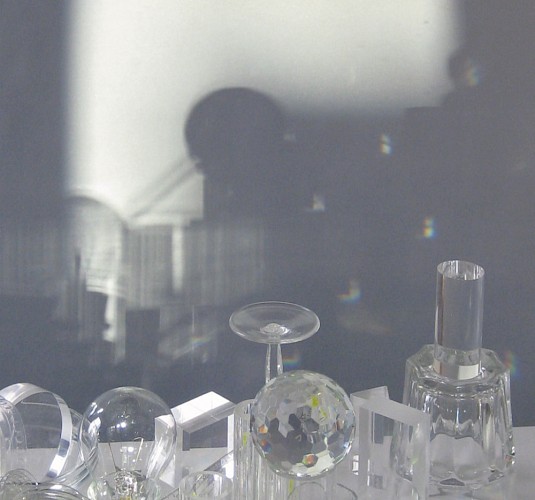

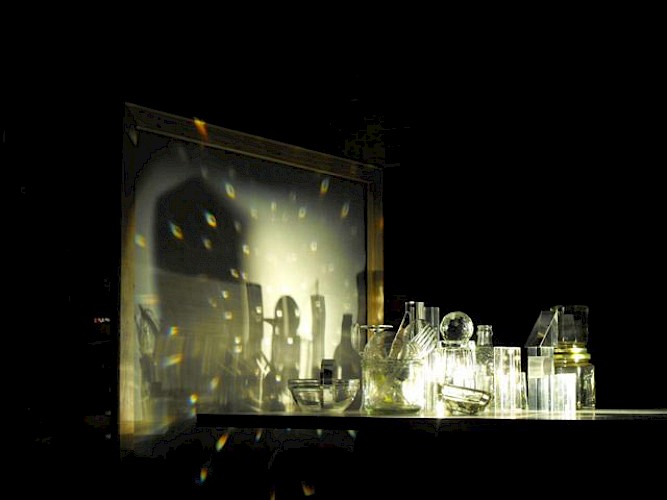

Light, movement and technical devices play an important part in Michaela Melián’s artistic practice. They are recurring elements of her multimedia installations.

In Lunapark Melián takes the concept of projection literally:

on a table she spreads out a landscape of transparent everyday objects (bottles, ashtrays, CD cases etc.) valuable glasses,

and prisms specially cut for the installation, and thoroughly shuffles established scales of value in this juxtaposition of the high

and the low, the exquisite and the casual. Illuminated by a slide projector with a rotating prism, the objects cast shadows on their surroundings, shadows that solidify as mutating constructivistic shapes reminiscent of a city skyline and dissolve again a moment later. The objects become lenses for a film-like flow generated by

a simple mechanical device that calls to mind Lászlo Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator (1930) and his concept of ‘The New

Vision.’ There is also an echo of the artist group Crystal Chain’s (1919/1920) utopian architectural designs that were directed toward a more humane society.

Michaela Melián’s gesamtkunstwerk of shadow, light and movement creates real and imaginary spaces of fleeting, fragile beauty. The installation becomes a tool for reflecting on perception and the issue of the transience and/or attraction of utopian visions—on the stage of Michaela Melián’s Lunapark they are

a definite attraction.

Heike Ander

Föhrenwald

Published in: Michaela Melián - Electric Ladyland, Lenbachhaus, 2016

Föhrenwald, a housing development on the outskirts of Wolfratshausen, was originally built as a showcase example of National Socialist housing policy. In 1940, it was converted into a camp for foreign forced laborers and conscripted German workers in the nearby munitions factories. After the war, it became an exterritorial housing facility for Jewish displaced persons: for more than ten years, survivors of the extermination and concentration camps who were unable to return to their native countries lived in the homes. The self-governed camp was eventually closed, and starting in 1956, German families who had been expelled from the eastern territories of the Reich were moved into Föhrenwald.

The development’s outward appearance has changed very little, despite its checkered history, which is best illustrated by the changing street names: “Danziger Freiheit,” or “Freedom of Danzig,” became “Independence Place” and finally “Kolpingplatz,” after

an early leader of the Catholic social movement. The houses, planned by architects hired under Nazi rule, have remained largely unaltered and even today typify the idyllic vision of the cozy single- family home.

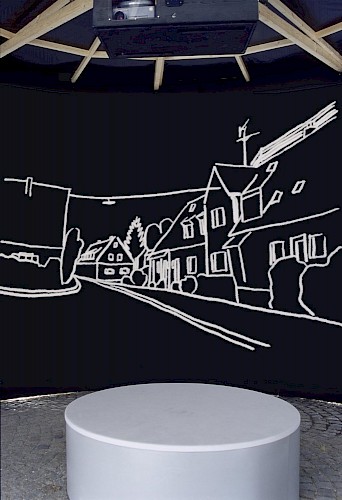

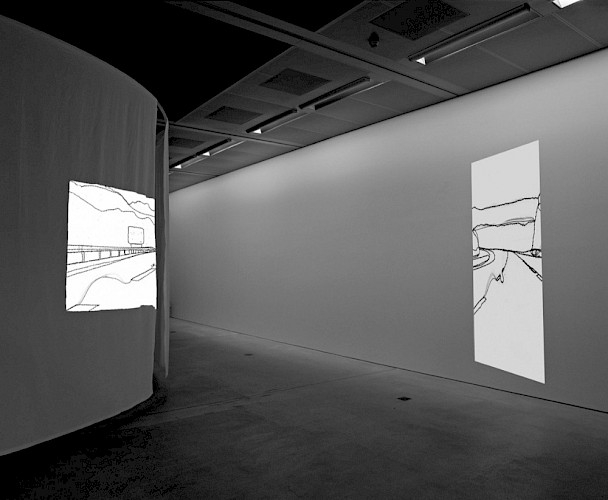

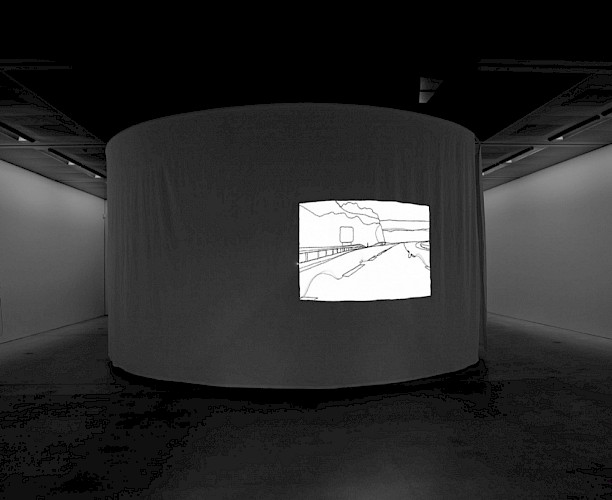

Michaela Melián’s Föhrenwald tells the story of the development (now known as Waldram) in the form of a multimedia installation: the environment features a slide projection in which drawings of the houses in white lines on a black ground visualize the area as it appears today. Hovering weightlessly in the dark room and slowly cross-fading into each other, they trace an imaginary stroll through the neighborhood. Superimposed on the looped series of images is an acoustic loop composed of spoken language and music.

Multiple voices tell stories from the different phases in the development’s history. The script is based on documents relating to the initial construction, the memories of forced laborers, and interviews with Jewish residents as well as the German expellees who moved in after 1956—some of their families still live there. Professional actors speak the edited interview texts in a neutral voice, while children read the historic documents. The polyphonic collage is embedded in a musical score whose even flow ties the different sources together. The composition weaves a dense sonic ambiance out of fragments—often no more than the static and scratching sounds, i.e., the playback noise—from shellac discs with works by Bach, Beethoven, Donizetti, Mendelssohn, and Schubert. The samples were taken from records released in Germany by the Jewish-owned companies Semer and Lukraphon in cooperation with the Jewish Cultural Federation between 1931 and 1938.

The soundtrack for Föhrenwald was produced by the department for radio plays and media art at Bayerischer Rundfunk. The radio play won the Online Award at the German federal broadcaster ARD’s Hörspieltage radio play festival in 2005. In 2006, it garnered the Hörspielpreis der Kriegsblinden, the most important award for audio art in the German-speaking world

Jan Verwoert

Michaela Melián, Life as a Woman, 2001

Published in: Frieze Magazine, London, 2002

Historical research has informed much of Melián's work of the last decade, which often pays tribute to women whose achievements have been misrepresented or forgotten. Life as a Woman, Hedy Lamarr (2001), for example, is a homage to the famous actress remembered for being the first woman to fake an orgasm on screen in 1933 and who later became a Hollywood icon. What is less widely known is that Lamarr invented the technique of 'frequency hopping' and donated the patent to the US army in 1943. Initially conceived as a safe method for the remote control of torpedoes, the technology was subsequently used to encode radio communication. Without it there would be no mobile phones. Images of Lamarr bathing nude and dressed in a glamorous robe were repeatedly printed on to the wall with rubber stamps to form a frieze. At the centre of the space was a wooden structure with a silk cover shaped like a submarine. The frailty of the construction stood in sharp contrast to the bombast of conventional monuments. The piece was a monument to Lamarr, but one that called into question the very idea of monumentality

Jochen Bonz

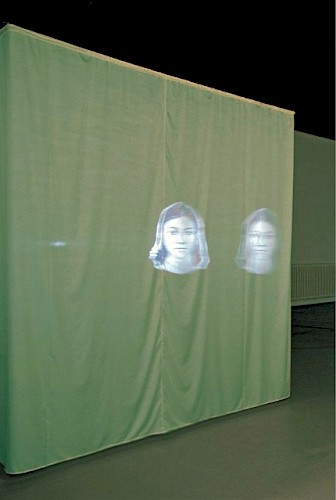

The Function of the Veil: On the Constitution of Meaning in a Work of Art by Michaela Melián

Published in: RISS: Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse: Freud–Lacan, Heft 52, Turia + Kant, Vienna, 2001

Is it possible to make a statement and at the same time, to address its conditionality? Can a contingency be expressed? Not to question what has been said, but to point out that it is indeed grounded upon a necessary assumption, that it takes place within a certain framework? Or, in a situation permeated by the feeling that the world is simply a construction, how can meaning be created at all? These questions are perhaps not explicitly posed, but they nevertheless pervade today's art. Everywhere, people are trying to question discourses and, at the same time, fabricate significance. This is also true for the artist Michaela Melián. In the early summer of 2001, Melián’s installation, Life as a Woman, created for the Böttcherstrasse art award exhibition at the Bremen Kunsthalle, puts the phallus on display. The work shows how the phallus, as a signifier, organizes the field, constructs a perspective, and creates meaning. Simultaneously, the installation utilizes the power of this signifier.

A room at an art show: in the center is a wooden scaffold about three meters long, covered in light beige silk taffeta. Due to its long shape and the characteristic dome in the middle, it is instantly recognizable as a submarine. Behind it, a blue-on-white stripe runs chest-high along the wall. Two alternating images are stamped in a row. They depict a woman’s upper torso coming out of the water and the same woman in different pose. Thanks to the rich contrast of the pictures (reduced to white and blue), the woman’s style of clothing, her gestures, and the fact that the two photographs continually alternate along three walls of the room, one is reminded of the movies – the 1920s and silent movies. The “film” leads to the third element of the installation: a cubicle, also covered with light fabric, about one-and-a-half by two meters wide and three meters tall. A picture of a woman’s head is projected onto the fabric, which is also light beige. It is easy to recognize the head from the film. Both film and projection meet at the same height. The head wanders over the fabric on the cubicle; in some places it appears fuller than it does in others; then, it is colorful and seems to stop moving, to stay still for a moment. One can enter the cubicle. Inside, one realizes that a slide projector is the source of the projection; it projects the image through a revolving prism. Once inside, the effect of the projection is even stronger.

The installation is entitled Life as a Woman and is by Michaela Melián. The fourth (or, apart from the title, the fifth) element of the installation is the following text, which the visitor can take from a pile of papers lying on the floor. These are like the information leaflets found in some museums.

LIFE AS A WOMAN

Hedy Lamarr, legally Hedwig Kiesler, was born on November 9, 1914, in Vienna.

In 1933, in the movie Ekstase, she simulated the first orgasm seen onscreen in cinematic history; in another scene, she swims naked in a lake. From 1933-1937, she was married to Austrian munitions factory owner Fritz Mandl. Afterward, she emigrated to the USA.

MGM’s Louis B. Mayer extolled Hedy Lamarr as the most beautiful woman in the world. In her first Hollywood film, she established a new type of woman in the American cinema: the exotic, dark-haired, enigmatic stranger. In her ex-husband’s Salzburg villa, the immigrant had seen plans for remote controlled torpedos, which were never built because the radio controls proved to be too unreliable. After the outbreak of the Second World War, she worked on practical ideas to effectively fight the Hitler regime.

At a party in Hollywood, Lamarr met George Antheil, an avant-garde composer who also wrote film scores. While playing the piano with the composer, the actress suddenly has an important idea for her torpedo control system. Antheil sets up the system on 88 frequencies, as this number corresponds to the number of keys on a piano. To construct it, he employs something similar to the player piano sheet music that he used in his Ballet Mécanique.

In December 1940, the frequency-switching device developed by Lamarr and Antheil was sent to the National Inventors' Council. A patent was awarded on August 11, 1942. The two inventors leave it up to the American military to figure out how to use it. Actually, Lamarr’s and Antheil’s Secret Communication System disappears into the U.S. Army’s filing cabinets. Finally, in 1962, as the Cuba crisis is brewing, the technology now known as frequency hopping is put to use. Its purpose is not to control torpedoes, but to allow for safe communications among the blockading ships – whereupon the principles behind the patent become part of fundamental U.S. military communications technology. Today, this technology is not only the foundation for the U.S. military’s satellite defense system, but is also used widely in the private sector, especially for cordless and mobile telephones.

It is possible to form an impression of Hedy Lamarr’s life from this installation. Yet if this were the only goal, it would have sufficed to simply display some brief biographical information. The installation space, essentially shaped by three elements (submarine, film, and projection), appears to be much broader, much larger. It is possible to situate Lamarr’s story in the space, yet the connotations of the story do not dissolve into the space, but remain around it, beside it. The space in Life as a Woman demands more: more general and more fundamental questions. To more closely define the space, I will start with the phallic quality of the submarine. A paradox is connected with it: the phallus must appear to be effective and at the same time, must be exposed as the effect of pure superficiality.

I stand in the room, which is created through the elements collected at the site, and feel certain that the submarine designs the room. Using it as the signifier, I perceive the line traced by the movement of the two female images as if it were the horizon, waves that have calmed. The nose of the submarine points to the projection room; it is located at the spot where, if elongated, the submarine would meet the film images. Seen this way, the two sides of the “film” and the submarine produce a triangle, whose top is the site where the female head is projected. Yet as a connotative space revealed by the work of art, it goes beyond biography (which is also doubtless one of the installation’s topics). The film, too, leaves the triangle as it extends behind the boat and moves along yet another wall. Accordingly, meaning always depends upon the connections produced in conjunction with both the artwork and the standpoint of the viewer. Simultaneously, the film constantly refers to the fact that the artwork is not exhausted in any of the interpretations. Or that at least the potential significance of the elements of the work is not exhausted in any of the manufactured contexts of meaning… The boat is an effective signifier; it has the shape of a phallus and is simultaneously not a phallus. It is just simply a fragile wooden scaffold covered in a taffeta veil. However, what purpose does taffeta serve, if not mainly to flatter the female figure for the benefit of the male gaze? Shouldn’t we rather see the function of the submarine as something expressing the female position in the symbolic, the site where the phallus exists simply as a lack of phallus? After all, the veil does not exactly force the phallus to disappear from the installation.

In his lecture on object relations, Lacan explains the function of the veil in connection with fetishism – that is, with an especially intense relation of the subject to an object, in which Lacan recognizes the function of the veil. The veil covers, as it is usually said. But to Lacan, the veil exposes. Materializing in the veil is that which makes an object valuable. The value of the object is not inherent, but exists externally. It is the thing that one never gets when one obtains the object. Or at least, it is the thing that never remains with one. The thing that creates desire, the pure significant, the signifier, the phallus. It sticks to the object; it is inside of it, but only because of its absence.

The idea that Lacan then develops takes its plausibility from the indisputable attraction of the veiled object. He says that “absence is projected onto and imagined in the veil.” This is what manifests in the veil: “a man idolizes his feeling about this nothing, which is beyond the object of desire… One could… say that through the presence of this curtain, something that appears to be lacking on the other side tends to be realized as an image. Absence is inscribed in the veil.”[1] It follows that the veil is the material the phallus uses to create effects. Yet it is also the visible limit where the power of the phallus fails. A wooden scaffold shaped like a submarine and covered in taffeta makes it clear that the phallus only exists when it produces an effect. The phallus itself has nothing inherent in it. However, in the symbolic dimension, in the framework of a symbolic order, in symbolic contexts, it has power. That means it requires a certain belief in order to give it meaning.

Life as a Woman is about creating meaning. How is meaning created? By creating a relationship. Things have meaning, when one believes in them. Let us take a love relationship as a somewhat elevated example. How is love created? According to Hesiod, Aphrodite or Venus, the ancient goddess of love, was made in order to create the world; her appearance is connected to the end of a multiple incest situation, a family knot in the worst sense. Overcoming this means setting up a symbolic order that creates desire using rules and laws, the result of a blow for freedom that gives rise to love as THE source of desire. Gaia has one of her sons cut off the penis of his father, Uranus. He throws his father’s body part into the sea, whereupon “white foam arose around the godly member, yet a virgin grew out of its midst.”[2] Aphrodite of the seafoam. From that moment on, she rides upon waves and shows us how to fall in love. Wherever she is, things have meaning, because one is connected to them, because for the subject, the love relationship makes everything meaningful. Love sweeps meaning along with it like a wave.

This constellation of the beginning of the creation of meaning is recreated in Melián’s installation. The elements are a phallus, conveyed and made recognizable as a phallus (and what does Uranus’ severed member represent but the member that is not simply a body part, but the symbolic phallus?!) and the smooth sea, which, in the projection, creates waves, so to speak, right where the image of Hedy Lamarr appears. Venus arises from the water, thus creating her presence and her function.

Melián’s work uses essential aspects of Lamarr’s life as a pivotal point. From this point, which I have described as a triangle, her particular life story can be told. Yet its elements have further significance. From the point where these reciprocal relations meet, the creation of desire can be presented, be narrated. I have tried to do this here. One should not overlook the notion that, because of the necessary relationship between the three essential elements (film, boat, projection), it is possible to always compare the potential interpretations instigated by the many connotations of the signifiers. These interpretations could be placed in relation to each other. So, for instance, in Lamarr’s real life story, the power of the submarine as a signifier is present, because it is also Hedy Lamarr, who, through her invention, has been given new meaning and visibility as a pioneer and patent owner.

Translation from German by Allison Plath-Moseley

[1] Jacques Lacan, Le séminaire, Livre IV: La relation d’objet, (Paris: Seuil, 1994) 155, quoted from the unpublished German translation by Gerhard Schmitz. An English translation is slated to appear later in 2003.

[2] Hesiod, quoted from the German translation of the collected works, Luise und Klaus Hollof, translators (Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin: 1994).

Frank Wagner

Low Tech–High Concept. The Reenactment of History and Personality in Michaela Melián’s Art Projects

In December 1998 the Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst Berlin mounted an exhibition titled „Fleeting Portraits—Flüchtige Portraits“, which included a work by Michaela Melián.

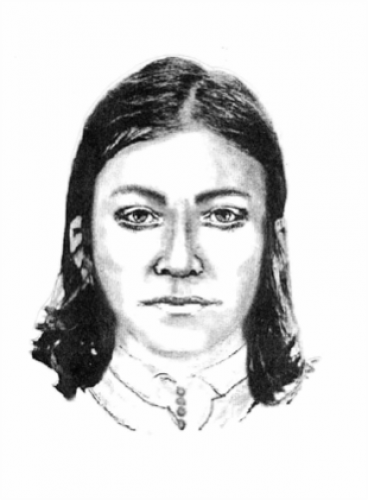

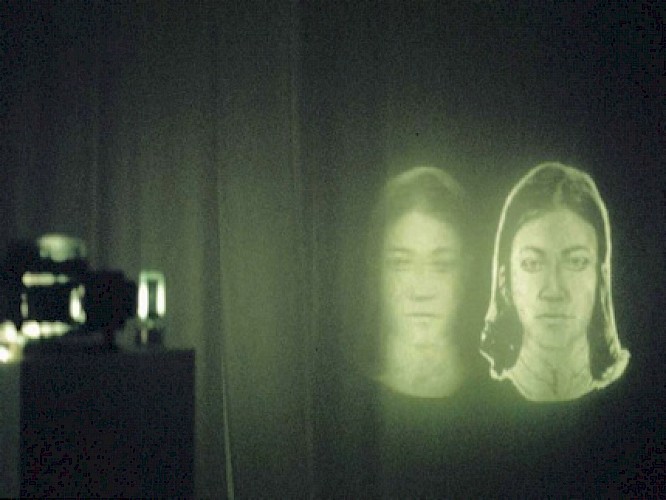

Portraiture and the portrait in the age of video was the theme, yet Michaela Melián’s surprising contribution was the best response to the exhibition’s title and topic, although it avoided all use of video technology. Instead, Michaela Melián took a trusty old slide projector and fixed a rotating mirror in front of its lens. The image this produced, at once static and in motion, was every bit as spell-binding as the many video images and computer animations projected in other rooms, whose brilliance and mobility are always impressive. The roving image easily beat all the static projections. Consisting of a cell-like cubicle of chamois-colored taffeta tacked to a square frame of wooden slats, and the projector and mirror on a pedestal at the center of the room, the installation was titled HysterikerIn/Anna O.(Hysteric/Anna O.).

Bertha Pappenheim

A good deal can be inferred from the artist’s decision to write the “HysterikerIn” of the title using a capital “I.” She does not subscribe to the medical profession’s historical, one-sidedly gender-specific construction of “hysteric” and the concept of identity resulting therefrom. Capital “I” in English is the first person singular pronoun, and thus represents the subject as a psychological category. The capital “I” in certain German nouns was adopted by feminists in their fight against sexist everyday language to preclude the linguistic discrimination of women and present them as equals. Yet the singular “I” makes no sense here, and the solecism calls into question the gender-specific concept “Hysterikerin.” This considered yet playful treatment of “I,” and the way it picks up current (not to say trendy) usage, cites, affirms and gently criticizes the humorously ironic character of pop aesthetics as well as taz newspaper house style.

Focal point of Michaela Melián’s installation was the portrait of Bertha Pappenheim, who went down in the history of psychoanalysis as “Anna O.,” and was thus deprived of a self-determining “I”.

Born in 1859 in Vienna, Bertha Pappenheim was treated for hysteria aged twenty-one by the Viennese physician Josef Breuer. Breuer described her case history and recovery in “Fräulein Anna O.” Anna O./Pappenheim discovered during one of their sessions that a particular symptom disappeared completely as soon as she described its first appearance. Grasping the value of this, she proceeded to describe to Breuer one symptom after another. Bertha Pappenheim called it the “talking cure.” Anna O. went so far as to reverse the doctor/female-patient relationship. It was she who decided what the subject matter was, asserting her right to narrate her sufferings herself. Breuer’s role became that of an interpretative listener. Apprised of the matter by Breuer, Sigmund Freud understood the significance of the new therapeutic set up, and he made it the foundation of psychoanalysis.

By making a moving slide projection of Anna O.’s face the focus of her silk taffeta installation, Michaela Melián raises the concept of projection central to psychoanalysis to the status of an artistic method. The portrait was constructed on the Munich LKA police computer’s facial-ID program on the basis of her description of a photo of Bertha Pappenheim. Since the program operates exclusively with male facial types and features the picture can only approximate the artist’s oral description. As in psychoanalysis, the final image is an abstraction mediated by language. The fact that this female portrait has been created from a description using male facial components also gestures at the physician/female-patient relationship.

Reconstruction and projection are the technical means by which a pioneering theory that radically changed bourgeois culture is imaged/reenacted. The impalpability of light, constant motion, and the way these brush the coordinates of a real-imaginary space that remains a mystery, function as metaphors for how personal biography is processed through language and memory.

The artist exploits the device’s technical simplicity and prima facie “correctness” to subtly imply that the procedure is perhaps simplistic and dangerous, as also—a criticism still frequently leveled against Freudian psychoanalytic treatment—that it fails to do justice to its patients. Bertha Pappenheim’s phantomlike appearance in the installation leaves us with the uncomfortable feeling that we are still laboring under the spell of a 19th-century Viennese therapy-success story as filtered through Anna O.’s eyes.

By setting the rudimentary Bertha Pappenheim portrait in motion and projecting it onto a soft, non-firm, translucent fabric, the artist also reenacts the way this particular acute female intelligence blurs and gradually crumbles into formulations for a therapeutic procedure and globally-recognized explanatory model of culture.

In the sequel, Bertha Pappenheim moved to Frankfurt, where she made a name for herself as a Jewish publicist, translator of feminist writings from English into German, and as a committed feminist. However, this political identity was razed from history in favor of her pseudonymic case history documented in Studien über Hysterie by Sigmund Freud and Josef Breuer (Vienna, 1895). Not that Melián herself dispels the unclarity surrounding biographical details. But then it is precisely this de-clarification that interests her, and that she makes visible for the beholder.

The projection is permanently visible in duplicate, as a static image and as a back-to-front, moving one cast by the rotating mirror. The two images will never merge, even if, repeatedly, they overlap for a brief instant. A short biographical text on Bertha Pappenheim accompanies the installation.

Early on in their analyses of the attacks on the World Trade Center, the media came up with the military-technical term “low tech–high concept.” The principle is typical of Michaela Melián’s general working approach, and is one that she always strives to achieve in her artistic work as the end product of her researches into complex matters of fact and their interrelations.

HysterikerIn/Anna O. // Bertha Pappenheim, Projektion is one of several monumental installations Michaela Melián has created in the past five years dedicated to important female celebrities. They all function along similar lines, and the employment in each of the same materials—fabric, wooden slats and a portrait—underline their thematic kinship.

Links

Michaela Melián: Föhrenwald - Hörspiel

Michaela Melián: Electric Ladyland - Hörspiel

Sammlung Stadler - Interview mit Michaela Melián: »In der Vergangenheit suchen wir die Zukunft«

Katrin Heise: Michaela Melián will Erinnerungen hörbar machen, Deutschlandfunk Kultur, 1.11.2024

CV

Solo Exhibitions (Selection)

2025

Passagen – Passages, Gare de la Blancarde, Marseille, France

Passagen – Passages, HYPC Veddel Space, Hamburg

Discothèque Le Corbusier, Cité Radieuse Le Corbusier, Marseille, France

2024

aufheben, Weserburg - Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen

Ulrichsschuppen, Galerie K’, Bremen

2022

Red Threads, KINDL, Center for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Tout ce qui sonne, Chambre Directe, St. Gallen, Switzerland

TeckTrack, cultural festival KulturRegiom Stuttgart, Kirchheim unter TeckPast Statements, Public Art Munich

2020

Chant du Nix, Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof, Hamburg

2019

Music From a Frontier Town, Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne

2018

Music from a Frontier Town, Public Art Munich

2016

Electric Ladyland, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich

2014

In a Mist, Badischer Kunstverein Karlsruhe

2013

Hausmusik, Gallery K', Bremen

2012

Lunapark, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

2011

Michaela Melián. Art Prize of the City of Nordhorn 2011, Städtische Galerie Nordhorn

2009

SPEICHER, Lentos Art Museum Linz, Austria

Ludlow 38 , Kunstverein München, Munich, Germany, Goethe Institute New York, NY, USA

2008

SPEICHER, Cubitt Gallery, London, UK

SPEICHER, Museum Ulm

2006

Föhrenwald, Kunstwerke, Berlin

Föhrenwald, Grazer Kunstverein, Austria

2004

LockePistoleKreuz, Kunstverein Langenhagen

2003

Street, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

Panorama, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck, Austria

2002

Ignaz Guenther House, Artothek Munich, Munich

Triangle, Springhornhof Art Association, Neuenkirchen, Germany

2001

Moda y desesperación, Goethe-Institut Madrid, Spain

1999

HysterikerIn/Automobile, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

HysterikerIn, Städtische Ausstellungshalle am Haverkamp, Münster

convention, The Better Days Project, Hamburg

1998

Bertha, Heart Gallery Mannheim

1997

Bikini, Kunstverein Ulm

1996

Gallery Francesca Pia, Bern, Switzerland

1995

Michaela Melián, Kunsthalle Baden-Baden

Tomboy, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

1992

Gallery Francesca Pia, Bern, Switzerland

Artothek Munich

Tanja, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

1989

Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

Exhibition participations (selection)

2025

Kybernetik. Vernetzte Systeme, Kunststiftung DZ-Bank, Frankfurt am Main

Sarah Schumann. Collages and Paintings from 1954 to 1982, Meyer Riegger, Berlin

2024

Oblique. Navigationen zwischen schrägen Winkeln und Schattenzonen, 8er Salon, Hamburg

Annual gifts 2024, km Kunstverein München

2023

in the Interim, Gallery K', Bremen

Yellow Memory, The War and Women's Human Rights Museum, Seoul, South KoreaSOUND AS MESSAGE, Museum Marta Herford

2022

Broken Music Vol. 2 70 years of records and sound works by artists, Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin

ÜBER:MORGEN - cultural festival on work, nature and technology - KulturRegion Stuttgart

past statements, public space, MunichTO BE SEEN. QUEER LIVES 1900-1950, NS Documentation Centre, Munich

Teck Track, Festival Kulturregion Stuttgart, Kirchheim/Teck

2021

Annual editions 2021, Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof, Hamburg

Annual editions 2021, km Kunstverein MunichAuf ins Kaff כפר, Syker Vorwerk, Centre for Contemporary Art, Syke

2020

Black Album / White Cube, Kunsthalle Rotterdam

Maria Luiko, Trauernde, 1938, past statements, öffentlicher Raum, München

What we are and what we do, Mitte Museum, BerlinOPEN DOORS | CLOSING DOORS, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

2019

Tell me about (yesterday) tomorrow. An exhibition on the future of the past, NS Documentation Centre Munich

Beauty!’, Gallery Gisela Clement, Bonn

Art sonor?, Museum Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona

Love and Ethnology - the Colonial Dialectic of Sensitivity (after Hubert Fichte), Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin

Annual editions 2019, Kunstverein München

Weissenhof City, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Girl Culture, Weissenhof Museum in the Le Corbusier House, Stuttgart

2018

I'm a Believer, Lenbachhaus, Munich

Ambitus. Art and music today, Kloster Unser Lieben Frauen art museum, Magdeburg

Germany is not an island. Contemporary Art Collection of the Federal Republic of Germany, Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, BonnBouncing in the corner. The Measurement of Space, Hamburger Kunsthalle

2016

Geniale Dilletanten, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg

2015

Go and play with the giant! Childhood, emancipation and criticism, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich

Vot Ken You Mach?, MWW, Muzeum Wspolczesne, Wroclaw, Poland

Geniale Dilletanten, Haus der Kunst, Munich

J'adore, Kunsthalle Lingen

The Present Order, Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst, Leipzig

2014

A House of Passive Noise, Ursula Blickle Foundation, Kraichtal

Illness as Metaphor, Kunsthaus and Kampnagel, Hamburg

Lichtwark revisited, Hamburger Kunsthalle

Yesterday the city of tomorrow, Urbane Künste Ruhr, Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr

HEIMWEH, STORE CONTEMPORARY, STORE, Dresden

P L A Y T I M E, Lenbachhaus, Munich

Radical Thinking, Münchner Kammerspiele, Munich

WHAT WE WANT TO SHOW, Kunstverein Heidelberg

2013

For the Time Being Hidden Behind Plaster, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden

Something of our own, Barbara Gross Gallery, Munich

12th Triennial of Small Sculpture, Fellbach

2012

The F-Word, Shedhalle Zurich, Switzerland

Change yourself, situation!, Stadtgalerie Schwaz, Austria

30 artists / 30 rooms, Neues Museum Nürnberg

The Sound of Downloading Makes Me Want To Upload, Sprengel Museum, Hannover

2011

BEGINNING WELL. ALL GOOD. ALL GOOD, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Switzerland

CAR CULTURE, Lentos Art Museum, Linz, Austria

2010

Home Less Home, Contemporary Art Museum on the Seam, Jerusalem, Israel

2009

Made in Munich, Haus der Kunst, Munich

2008

Recollecting. Looted Art and Restitution, MAK - Austrian Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna, Austria

Art on Air - Radio Art in Transition, Neues Museum Weserburg Bremen, Bremen

2007

Meerspraak I - Multispeak I, Witte Zaal, Ghent, Belgium

Mistake #6, Jet, Berlin

För hitz ond brand, Contemporary Art in Appenzellerland, Switzerland

TALK/SHOW, tranzit dielne, Bratislava, Slovakia

It is difficult to touch the real, Grazer Kunstverein, Austria

2006

The Eighth Field. Gender, Life and Desire in Art since 1960, Museum Ludwig, Cologne

On the Absence of the Camp, Kunsthaus Dresden

2005

Zur Vorstellung des Terrors: Die RAF Ausstellung, Kunstwerke, Berlin

Ongoing Feminism & Activism, Gallery 5020, Salzburg, Austria

Overreaching, Motorenhalle Dresden

Crime Scene and Phantom Image, Cinestar Weimar

Bltanski, Ganahl, Melián, Börnegalerie, Frankfurt am Main

2004

Neue Galerie im Landesmuseum Joanneum, Graz, Österreich

Common Property/Allgemeingut, 6. Werkleitz Biennale, Halle/Saale

Arno Schmidt, Vier mal Vier, Fotografien aus Bargfeld, Ulmer Musum

Atelier Europa: Ein kleines postfordistisches Drama, Kunstverein München

Gegen den Strich. Neue Formen der Zeichnung, Kunsthalle Baden-Baden

Arbeiten auf Papier, Sprüth Magers Projekte, München

NEURO, Make-World-Konferenz, München

2003

Momente in der Schwebe, Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (NGBK), Berlin

Lieber zuviel als zu wenig, Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (NGBK), Berlin

Analog/digital, Hyper Kult 12, Universität Lüneburg

now and forever, Luitpoldblock, München

Griffelkunst, Griffelkunst-Vereinigung Hamburg

2002

Import/Export, Villa Arson, Nice, Frankreich

Intermedium, ZKM Karlsruhe

Die zweite Haut, Museum Bellerive, Zürich, Schweiz

Cardinales, Museo de Arte Contemporánea de Vigo, Spanien

2001

Musdienu Utopija -Contemporary Utopia, Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art/ Arsenals, Riga, Lettland

Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße in Bremen, Kunsthalle Bremen

Ich bin mein Auto, Kunsthalle Baden-Baden

CTRL (SPACE), ZKM Karlsruhe, Deutschland

Die zweite Haut, Museum Evelyn Ortner, Meran

2000

Die verletzte Diva, Galerie im Taxispalais, Innsbruck, Österreich

Produktivität und Existenz, Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin

Politeia, Aspekte Galerie Gasteig, München

Essensbilder, Manzini Mitte, Berlin und Galerie Dörrie*Priess, Hamburg

The Biggest Games in Town, Lothringer 13, Munich

Import/Export, Kunstverein Salzburg, Österreich

Import/Export, Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Arnhem, Dänemark

1999

Dreamcity, Kunstverein, Kunstraum, Villa Stuck, München

Borderline, Museum van Bommel van Dam, Venlo, Niederlande

1998

Das rote Zimmer, Galerie Francesca Pia, Bern, Schweiz

Von hier aus, Barbara Gross Galerie, München

%, Galerie Inga Kondeyne, Galerie Rainer Borgemeister, Berlin

Circuitos d’ Água, Museu de Eectricidade, Lissabon, Portugal

Fleeting Portraits / Flüchtige Porträts, Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst (NGBK), Berlin

1997

Bridge/The map is not the territory, Projekt der Arbeitsgemeinschaft Fleetinsel auf dem Fleetmarkt, Hamburg

1996

Deutscher Kunstpreis der Volksbanken und Raiffeisenbanken, Kunstmuseum Bonn

Nassauischer Kunstverein, Wiesbaden

Pinakothek der Moderne, Staatsgalerie Moderner Kunst, München

Orte des Möglichen, Hypobank International S.A., Luxembourg,Achenbach Kunsthandel, Düsseldorf

1994

Scharf im Schauen, Haus der Kunst, München

1993

Die Arena des Privaten, Kunstverein München

Utopische Kunst/Künstliche Utopie, Verein Kunst Werk, Friedrichshof, Österreich

Diskografie

2025 | Music for a While | a-musik, Köln

Tania | 2022 | LP | KINDL, Berlin

Music From A Frontier Town | 2018 | CD + LP | Martin Hossbach, Berlin

Speicher | 2016 | CD | intermedium records, Munich

Electric Ladyland | 2016 | CD + LP | Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich

Monaco | 2013 | CD + LP | Monika Enterprise, Berlin

Los Angeles | 2007 | CD + LP | Monika Enterprise, Berlin

Convention Manifesto | 2007 | LP, Monika Enterprise, Berlin

Föhrenwald | 2006 | CD | intermedium records, Munich

Baden-Baden | 2004 | CD + Doppel-LP | Monika Enterprise, Berlin

Locke Pistole Kreuz | 2003 | Mini CD

Collections

Bundeskunstsammlung, Bonn

Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich

Lenbachhhaus, Munich

Hamburger Kunsthalle

Galician Center for Contemporary Art, Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Lentos Kunstmuseum, Linz, Austria

Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

Kunstpalast Düsseldorf

Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München

Artothek München

Tiroler Landesmuseum, Innsbruck, Austria

Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst, Leipzig

Studienzentrum für Künstlerpublikationen / Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst, Bremen

Kunststiftung DZ-Bank, Frankfurt am Main

Munich Re Art Collection

Sammlung Deutsche Bank

Karin und Uwe Hollweg Stiftung, Bremen

Sammlung Gabriele und Wilhelm Schürmann, Herzogenrath

Sammlung Stadler, Munich

Sammlung Ioannis Christoforakos, Munich

Prizes and Awards

2019

Rolandpreis für Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, Bremen

2018

Edwin-Scharff-Preis, Hamburg

2012

Grimme Online Award für Memory Loops

2011

Kunstpreis der Stadt Nordhorn

2010

Kunstpreis der Stadt München für Memory Loops - 300 Tonspuren zu Orten des NS-Terrors in München 1933-1945

2009

Hörspiel des Jahres der Deutschen Akademie der Darstellenden Künste für Speicher

2008

Hörspiel des Monats Januar 2008 im Bayerischen Rundfunk für Speicher

2006

Hörspielpreis der Kriegsblinden für Föhrenwald

1996

Bayerischer Staatsförderpreis für Bildende Kunst

1995

Förderpreis zum Internationalen Preis für Bildende Kunst des Landes Baden-Württemberg 1995

1994

Förderpreis für Bildende Kunst der Landeshauptstadt München

1993

Förderung Hochschulprogramm II für Künstlerinnen

Werkstipendium des Kunstfonds, Bonn

1984

DAAD-Stipendium, London, UK